Part One

- thebombersblog

- Sep 3

- 9 min read

Attacking this year.

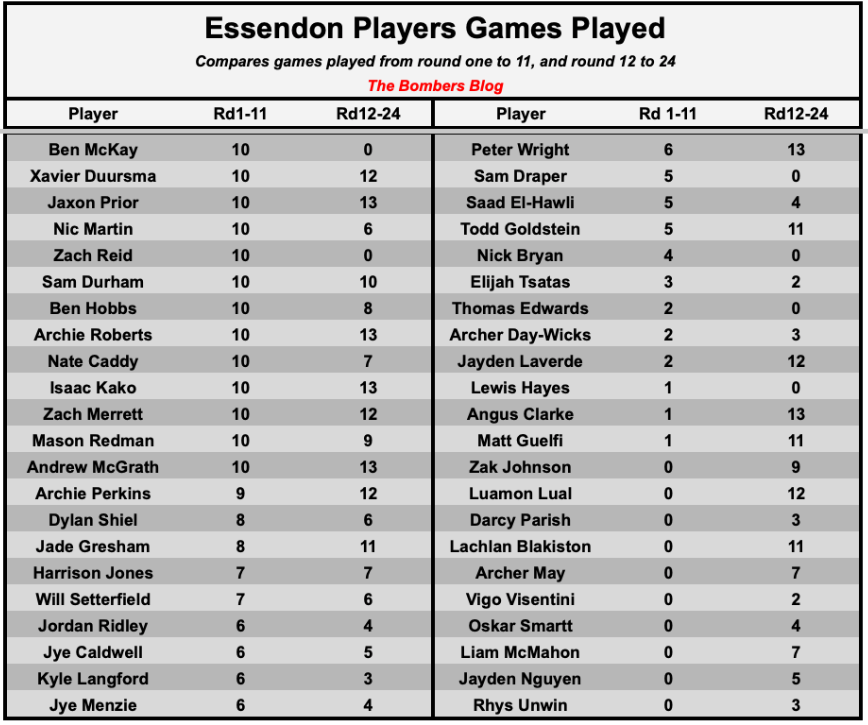

Reviewing Essendon’s 2025 season as a single body of work feels almost impossible, as from roughly the halfway point continuity in the weekly lineup was tested by injury, with the disconnection between each line compounded by the reality of using 44 players across the year.

With that in mind, I’ve split this review into two sections. The first covers the opening 10 games, from Round 1 through to the Dreamtime clash in Round 11. The second starts at Round 12 against Brisbane, where I believe the injuries began to have the greatest effect on performance, and runs through to Round 24.

I believe this gives the fairest picture of where Essendon sits in year three under Brad Scott.

My aim, as always, is not to judge purely on outcomes, but to focus on the processes year on year: what held up when the side had a reasonable chance to execute, and what broke down even under the best possible circumstances.

What these changes looked like.

In the first 10 games, both first-choice ruckmen succumbed to season-ending injuries, with Nick Bryan managing fewer than four full games and Sam Draper less than five.

But it was after Round 8 that the team’s structure began to change dramatically, with the most significant disruptions concentrated behind the ball.

Jordan Ridley would miss the next eight games, and his replacement, Lewis Hayes, lasted only a single quarter before his year ended. Just two weeks later, the other key defenders who had played every match up to that point, Zach Reid and Ben McKay, would also finish their year far too early.

In the same Round 11 clash against Richmond, Kyle Langford featured for the final time before returning 11 weeks later, while his front-half teammate Harrison Jones wouldn’t make another appearance after Round 8 for the rest of 2025.

Darcy Parish and Jye Caldwell were the two main midfielders missing to start the season, with Parish finally returning to full fitness and available for selection at Round 13, only for his year to end three matches later. Caldwell missed five games between Rounds 3 and 9, finishing his campaign at Round 17, and a week later, fellow midfielder Will Setterfield was also done, the same week Nic Martin suffered a 12-month knee injury.

The young ones.

Seven rounds into the season, Essendon had debuted three players, Isaac Kako, Saad El Hawli and Tom Edwards (whose year was cruelly cut short by injury) — but from Round 9 onwards, as injuries mounted, the club was forced to call on another 12, including four fresh recruits from the mid-season draft after Dreamtime.

In the last 13 games of the season, Essendon relied heavily on its newcomers to fill the void left by injuries, with Angus Clarke playing all 13, Luamon Lual 12, Lachlan Blackiston 11, and Zak Johnson nine. Liam McMahon and Archer May featured in seven each, while Jayden Nguyen played five. Alongside them was Kako, remarkably playing every game of his debut season after just a single full pre-season, one of only four Bombers to do so, alongside Jaxon Prior in his first year at the club.

The reliance on so many inexperienced players made the second half of the campaign a constant challenge, not just week to week, but quarter by quarter, providing vital context when assessing performance.

This comparison covers the key performance indicators I’ve tracked over the past three seasons, including some of the basics in disposals, clearances, contests and marks, as well as ball movement, defending transition, inside-50 efficiency, score sources and more.

Quarters.

We’ll start with the outcome of those processes, the average scores for and against in each quarter.

• Overall, Essendon won just five first quarters for the season, with only one of those coming after the Round 11 Richmond clash, in Round 22 against St Kilda.

• Their highest-scoring first quarter was 37 points against North Melbourne in Round eight, a team who only won six opening terms for the season. Their next best was 22 points against Melbourne in Round 5.

• Up until Round 11, the Bombers conceded five or more goals in a first quarter on four occasions. Three of those were against top nine teams in Hawthorn, Adelaide and the Western Bulldogs, with the other against wooden spooners West Coast.

• Post Round 11, they gave up five or more goals five times, four of those to top nine teams in Brisbane, Geelong, Western Bulldogs and Gold Coast, with the other to Carlton in Round 13.

• Between Rounds 12 and 24, Essendon averaged just over 24 points to half time. In this span, they failed to kick a goal in the second quarter three times, and on four other occasions managed only one goal in the same 20 minutes.

• As you’ll read in future reviews, scoring from opposition turnovers is the main score source of modern football, but in first halves up until Round 12 the Bombers averaged only 5.4 shots from this, well below the AFL average of 7.02

• Essendon’s three highest-scoring second quarters came against Sydney in Round Nine, Collingwood on Anzac Day and Fremantle in Round 15. In those games, 13 of the 20 scoring shots came from intercept, accounting for 68 of the 95 points.

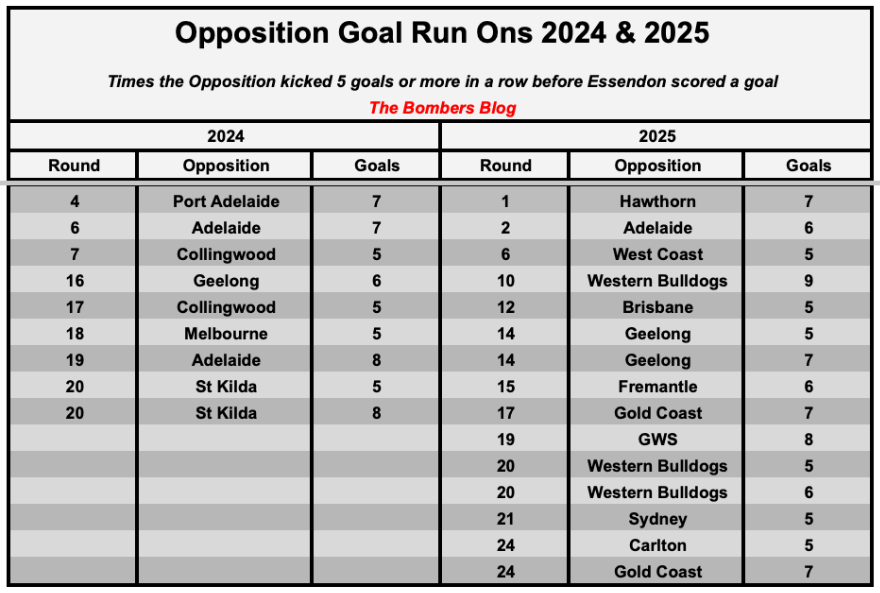

• Last year, Essendon conceded five-goal runs on nine occasions, with only three before the bye. This year, they conceded four to Round 11, before allowing 11 in the run home.

• The longer the games went on against such a young lineup later in the season, the more the opposition took advantage, as Essendon conceded over 52 points in second halves, up from 40.2 in the first 10 games. By comparison, the previous two seasons saw opponents average 40.7 and 43.7.

Overview.

Getting off to a strong start in first quarters is obviously crucial, as scoreboard pressure forces opposition coaches to adjust their default structures and methods they have trained for all season, as well as the plans they have prepared during the week.

As we saw, this was asked far too many times of Essendon this year, requiring readjustments at the first break, either through increased attack via run, carry, and handball, or through positional tweaks as the midfield mix demanded a different look.

At times last season, these adjustments were effective, but this year it frequently took until the third quarter before any meaningful impact, such as against Brisbane in Round 12 and Carlton the following week.

As explained earlier, the poor second halves as the season wore on were largely a reflection of the age profile and experience, with onfield leadership in assessing what was required at key moments sorely missed, and certainly not helped by the occasional frustration of the more experienced players.

On occasions, it was striking how there was a void of senior voices in each line, with no onfield coach able to regroup the players after conceding goals, better control the game through changes of tempo, or even provide a basic lift in morale to refocus the team.

I’m not convinced that among the players missing in the defensive third there is a natural leader capable of “steering the ship.” The closest is Andrew McGrath, who was required to play as a midfielder when rotations demanded, so a return to the back half will be crucial in 2026.

The Captain is the obvious choice, demonstrating leadership through actions both in attack on the ball and defensively against the opposition, but he appears to carry too much without sufficient support alongside him.

More experience will most likely need to be added over the off-season, while some of the players who have been in the system long enough must step up, find a voice, and contribute selflessly and consistently, rather than only when it suits them.

Disposals.

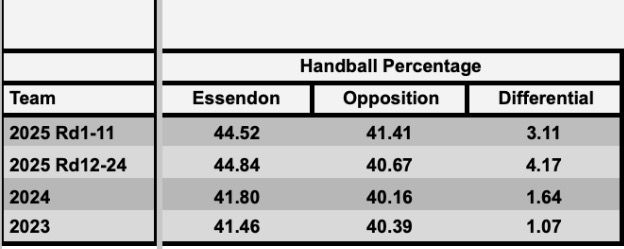

This is the first sign of the system change I noticed back at preseason training, and wrote about multiple times in previews and reviews throughout the season. Here I will go into more detail on how this looked, with the effectiveness of it to be broken down in later sections covering other areas.

• Some big disposal differential numbers to start 2025 continued on from last year, when Essendon ranked number one in this metric. Only three times did they finish in the negative up until Dreamtime, all of which were losses to Adelaide, Collingwood and the Western Bulldogs. Included in these 10 games were positive differentials of 94, 96 and 100 against Melbourne, Sydney and Richmond. But in the seven games where Essendon had more disposals than their opposition, they lost the territory count in four.

• After Round 11, things changed dramatically with a turnaround of almost 58 disposals, 34 of those by foot. In that stretch, Essendon only gained more territory than their opponents in three games, versus Richmond, Carlton (Round 13) and St Kilda.

• No team had a lower kick-to-handball rate than Essendon this year. That has been a recurring trait over the past five seasons, with the Bombers ranked in the bottom five of this category every year in that span. At the other end of the spectrum, the top three sides on the ladder this season had the highest kick-to-handball rates, continuing a trend from last year when four of the top five sides in this measurement also finished inside the top four.

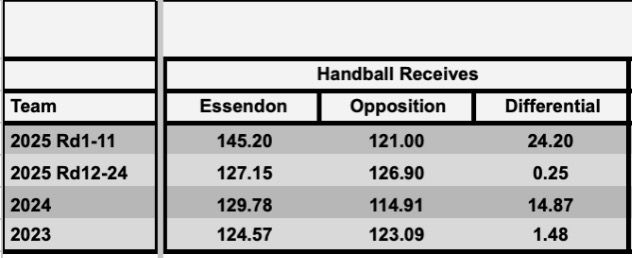

• By Round 11, Essendon’s 145.2 handball receives per game was clearly number one in the league, and if maintained over the course of the season, would be well clear of the Western Bulldogs in second on 131.

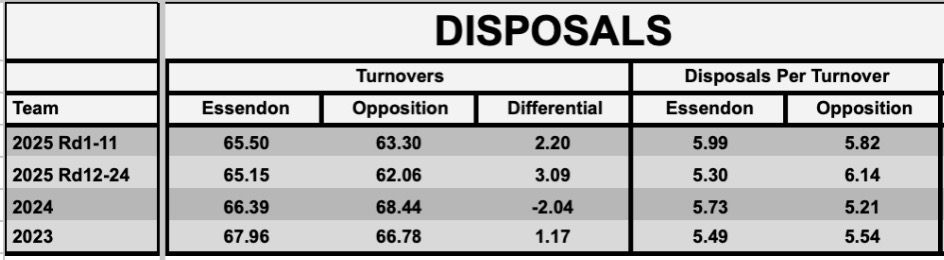

• Disposals per turnover also dropped sharply in the final 13 games compared to the opening block, with most of that coming via hands. The consequence was losing the ball closer to the source, rather than further down the ground through field position gained by foot.

• Essendon had previously been one of the safest teams with ball in hand, ranking inside the top four for disposals per clanger (a disposal, kick or handball, that goes directly to the opposition, a dropped mark under no pressure, or conceding a free kick or 50-metre penalty) in each of the past three seasons alongside Fremantle and the Bulldogs. But in the second half of 2025, their rate of 6.08 would have ranked fifth worst, ahead of only Sydney, Port Adelaide, Adelaide and West Coast. While Adelaide sat 17th for their own disposals per clanger, they were number one in forcing their opponents into the fewest.

Overview.

Last year saw a major difference in the team’s ideology and method compared to 2023, with the game built more around a front-half press. That approach was partly born out of necessity, as Essendon weren’t efficient in turning initial forward 50 entries into maximum points, which meant they needed to ‘build a wall’ to prevent the opposition rebounding out.

This year brought a significant shift, with handball emerging as the preferred style of ball movement. That change was linked to supporting the source with extras, often through half-forwards such as Nic Martin, Sam Durham, Ben Hobbs, Archie Perkins, Jade Gresham and others rolling up between the arcs to help intercept or win clearances at stoppages.

With this setup, the right decision is to chain up by hand, using those numbers in transition to carry the ball forward and “come at” the opposition, who usually kept a defender back behind the ball rather than following their direct opponent.

In turn, the way Essendon exited stoppages became critical, with a premium placed on getting the balance right inside the contest by players not overcommitting, and with outside-in positioning to be available as an option to receive.

The questions then became: are the players reliable enough to get that balance right at the source? Are they smart enough to find the right outlet by hand and not kick long to outnumbered contests ahead?

Quote taken from my preseason preview in November 2024.

“The ball is constantly in motion via quick hands but is moving forward instead of sideways and backward. It’s forcing players to be on the move to receive and have multiple possessions in chains rather than giving off and not following up… It not only creates space around the players in motion but also encourages those ahead to move and anticipate where the ball is likely to go. This change will challenge decision-making on who to give it to and when to kick, while also testing the forwards’ timing in starting their leads.”

The next important stage is capacity to run, and to run at speed.

Once the ball is “out,” players must spread quickly to make the ground “big,” opening multiple forward options instead of being predictable in their direction of attack.

Here, the best teams play expansive football, spreading far and wide. That not only creates space, but also gives forwards the chance to separate from each other and create more genuine one-on-one battles.

Now the fitness element comes into play: can Essendon sustain the repeat efforts to “wave run” alongside teammates, carry the ball further, and get from contest to contest?

Earlier I noted the top three teams had the highest kick-to-handball rates this year, their advantage lies in superior work rate.

When they do go by foot, they’re able to get to the next contest, evening up numbers or even outnumbering the opposition in defence.

But this is only one aspect — how you use it.

As the handball game ramped up through the season, so too did opposition pressure. That often restricted Essendon’s ability to exit cleanly, forcing, most of the time, younger Bombers to simply transfer that pressure to a teammate and keep that heat in the vicinity.

When the ball was eventually turned over, the challenge became how quickly players could switch from ball winning to locating an opponent. That shift is aided by maintaining balance around the area, rather than getting too far ahead of the play too soon in assuming teammates were already “out”.

Coming up next.

Part two: a deep dive into the stoppage game and how things shifted when the first-choice rucks were sidelined, along with a closer look at possessions, both contested and uncontested, for and against.

Comments