Part Five

- thebombersblog

- Nov 9, 2025

- 10 min read

Intro.

Following on from parts one https://thebombersblog.wixsite.com/thebombersblog/post/2025-vs-2024-vs-2023

two

three

and four

this is the continuation of my review into Essendon’s 2025 season. A season marred by injuries that, in my view, was too difficult to assess as a whole. Instead, I’ve chosen to break it into two key sections, up to Round 11, where I believe the team had its best opportunity to demonstrate both the ideology behind its plans and the method to suit; and from Round 12 onwards, where the injury toll became too great to fairly measure what the side was truly capable of.

Marks.

Never has marking held greater influence over the game than it does today. In past eras, its value was tied mainly to creating scoring opportunities inside 50 or enabling ruckmen to control the air. Now it shapes almost every aspect of how teams move the ball and defend.

Marks are central to transition, controlling tempo, shifting angles of attack, and drawing defenders out to open space. Just as important is how sides win the ball back to create those chances, as intercept marking has become a key mechanism for regaining territory and setting up field position, giving teams one of their best opportunities to dictate the game with ball in hand.

Winning it the hard and easy way, for and against.

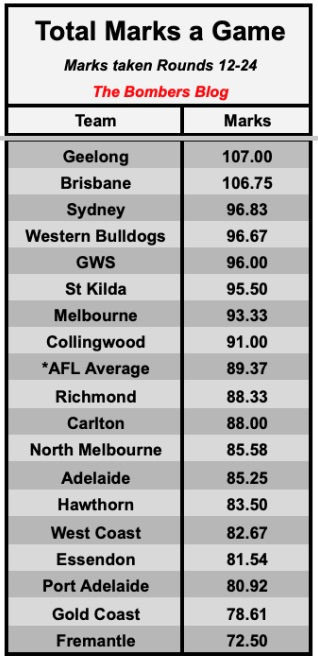

• From 2022 to 2024, only St Kilda averaged more marks per game than Essendon’s 99.16.

• By Round 11 this season, the Bombers’ 95.3 marks ranked third behind Brisbane and Melbourne. Across the final 13 games, that number dropped to 81.5.

• Last year, Essendon finished the season with a +5.87 mark differential. Up until Round 11 this year, it was -4.3.

• 2024, the Bombers ranked 8th for disposals per mark, with four finalists ahead of them. After 10 games this year, their rate slipped to 9th, again with four finalists ranked higher.

• In their first 10 games, Essendon averaged 103.3 marks in wins, compared to 83.2 in losses.

• Up until Round 11, Essendon games featured the most marks on average, with 194.9 in total from both teams. From that point until the end of the season, it was 193.5.

• After Round 11, no team conceded more marks than Essendon’s 112 per game, with a 30.4 differential easily the largest in that stretch.

• Nic Martin and Zach Reid averaged 8 and 7.7 marks respectively across their first 10 games, ranking 5th and 7th in the league at that stage of the season. Peter Wright was the next Bomber, sitting 45th among all players to have played at least four games.

Winning it the hard way.

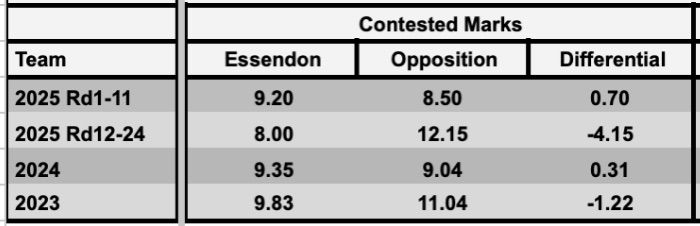

• The AFL average for opposition contested marks until Round 11 was 8.78, with Essendon just keeping their opponents below that at 8.5. Over the final 13 games, however, no team conceded more than the Bombers’ 12.15.

• After 11 games (10 for Essendon and Gold Coast), Ben McKay’s 1.4 contested marks per game ranked ninth among all defenders. Unfortunately he wouldn’t play again, but had he maintained that rate, only Sam Taylor (GWS) and Esava Ratugolea (Port Adelaide) would have averaged more.

• Of all forwards to have played at least four games up until Round 11, Sam Draper, Peter Wright and Nate Caddy ranked 5th, 12th and 19th respectively for contested marks in the front half.

• Of all forwards to have played at least four games up until Round 11, Nate Caddy was the second youngest among the top 75 for contested marks per game.

Winning it the easy way.

• In their first 10 games, Essendon averaged 95.1 uncontested marks in wins, compared to 72.5 in losses.

• In 2023, Essendon had the second-lowest rate of disposals per uncontested mark, behind only Brisbane. In 2024, they ranked sixth-lowest, and by Round 11 this year, eighth.

• The AFL average for uncontested marks per quarter was 20.15 in 2023 and 20.72 in 2024. By Round 11 this year, that average sat at 19.82. Over the same period, Essendon had exceeded that average in just 24 of 40 quarters, while their opponents had done so in 27 of 40.

• Across the first four rounds, Essendon conceded an average of 103 uncontested marks per game. In those games, each opponent was allowed to take more uncontested marks than their eventual season average, Hawthorn almost 19 more, Adelaide 36 more, and Port Adelaide just under 36 more.

• Across the entire season, Essendon restricted their opponent to fewer uncontested marks than their season average only twice, once before Round 11 against North Melbourne, and once after Round 12 against St Kilda.

• After 10 games, the Bombers averaged 76.1 uncontested marks in transition from the back two-thirds of the ground, the third most of any team, following 77.3 last year (also third) and 79.2 in 2023 (second). Across the final 13 games of this season, they averaged only 63.5, the third least in the competition, and more than 20 fewer per game than their opponents.

The front third.

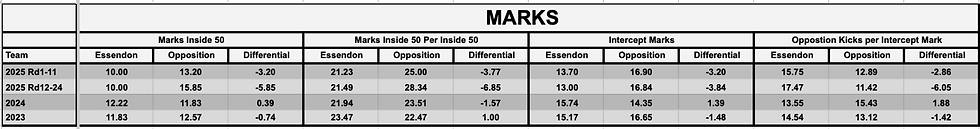

• Essendon improved from 12th for marks inside 50 in 2023 to 9th in 2024. After 10 games in 2025, their average of 10 per game ranked 15th. In the final 13 games, they also averaged 10 per game.

• From their first 10 games, Essendon took five or more marks inside 50 in only five quarters, none against eventual finalists. In their final 13 games, they managed it five times, four against eventual finalists: Brisbane (Q3), Fremantle (Q2), GWS (Q4) and Geelong (Q3).

• Peter Wright ranked 16th of all players (minimum four games) for marks inside 50 after the first 10 rounds. Jye Menzie was next for Essendon in 50th, with Sam Draper 57th.

• Wright’s Best and Fairest-winning 2022 remains the only season in which he averaged more marks inside 50 than his 2.33 up to Round 11 this year.

• Up until Round 11, Nate Caddy ranked 68th for marks inside 50 with 1.2 per game (minimum four games). Of those 68 players, he was the third youngest.

• Last year, the Bombers found a marking option inside their front third on just under 22% of entries, ranking 12th. Across their first 40 quarters this season, they bettered that rate in only 17.

The back third.

• Only West Coast and Richmond conceded more marks inside 50 than Essendon’s 13.2 across their opening 10 games.

• In the previous two years, Essendon conceded a mark inside 50 from 22.4% of opposition entries in 2023 and 23.5% in 2024. By Round 11 this year, 25% of entries ended this way.

• The AFL average for marks inside 50 per inside 50 entry from the first 10 rounds was 22%. Across those 40 quarters, Essendon held their opponents below that rate just 14 times.

Defending the air.

• Essendon averaged 13.7 intercept marks per game to Round 11, ranked 14th, with only North Melbourne, St Kilda, Sydney and West Coast averaging fewer. Of the eventual finalists, only Fremantle and GWS were below the AFL average at that point.

• The AFL average for intercept marks after 10 games was 14.86. Not once did Essendon better that in any of their first four games. But in the next six, only once did they not, averaging 15.5.

• Across the final 13 games, Essendon averaged 13 intercept marks a game, with only North Melbourne and St Kilda ranked lower.

• From Rounds 12 to 24, the AFL average for intercept marks was 15.05. Essendon exceeded that only three times — against Richmond (Round 18), GWS (Round 19) and Geelong (Round 22).

• In 2023, Essendon ranked 15th for opposition kicks per intercept mark, with seven of the top nine sides making finals. In 2024, they improved to eighth, with six of the top nine also finalists. By Round 11 this year, Essendon had slipped to 17th, with six of the top nine again qualifying for finals.

Overview.

Intent.

If you’ve read earlier parts of my 2025 review, you’ll understand the changes outlined in Essendon’s default method with the ball. The deep dive into marking details that shift even further, highlighting how the “control” of the previous three seasons, particularly the last two under Brad Scott, looked markedly different up until Round 11.

There were still games that required a stronger emphasis on kick-mark control, some by design to counter specific opposition styles, others forced by poor starting positions of possession chains after clearance losses or breakdowns in defending transition.

Essendon took 100 or more marks in 13 games last year, but only five times in 2025, four of which came in the first 10 rounds. Their season-high of 126 marks came in Round 9 against Sydney, where the plan was clearly to exploit the Swans’ tendency to retreat defensively. The same was evident two weeks later against Richmond, as the Bombers stretched the Tigers’ youngsters across the MCG for three quarters before breaking them down in the final 20 minutes.

Against the Bulldogs in Round 10, their 90 uncontested marks, the sixth-most of the season, were largely a response to territory lost from stoppage, where they lost the clearance count by 12 in the first three quarters.

Later in the season this became much more common: -18 from stoppage against Fremantle (Round 15), -11 versus Carlton (Round 24), and -9 the week earlier against St Kilda. In those games, Essendon were forced to slow their ball movement through the back two-thirds, averaging 74 uncontested marks in those zones, 11 more than their season average, and only three and five fewer than their 2023 and 2022 figures respectively.

Ideally, Essendon would find a better balance between the ball movement methods of the previous two seasons and this year’s approach. The kick-to-handball ratio at key moments, along with the number of players committed to the source, remains a major factor.

Understandably, as injuries mounted and more first-year players were required to fill gaps, Essendon’s work rate dropped in finding easy outlets, both laterally and, more importantly, ahead of the ball. That meant going to more contests by foot, as fatigue increasingly affected decision-making and execution, resulting in more turnovers and a susceptibility to being punished on the scoreboard.

In the previous review I detailed speed of ball movement, specifically comparing Brisbane and Essendon in turning a possession into a disposal when looking to find an uncontested marking option.

The Lions showed their default to “lower their eyes” and a willingness to honour their teammates’ work to spread wide through leg speed, opening spaces for others to move in and out quickly and forcing opponents to work much harder to deny viable options.

Essendon needs to improve this in multiple ways, mainly through list management in finding players with natural speed as well as through fitness levels, with keeping players fitter for longer obviously a requirement.

Winning it back.

Quote taken from my review of Round 15 versus Fremantle

Up until Round 11, Essendon averaged 15.6 intercept marks per game — the 8th most in the competition at that point. McKay led the group with 2.5 per game (22nd among all players to have played at least three games), followed by Reid with 2.1 (32nd), Ridley and Prior with 1.5 each (63rd and 64th), then Draper and Redman both with 1.2…

…In the four games since, the Bombers have averaged just 9.25 intercept marks, with Prior the only player from that list to play in each of the last three.

Poor defending of the opposition’s ball movement once again, even up to Round 11, as covered in Part Four, meant a heavy reliance on the second and last line defenders to not only hold their direct matchups and prevent scoring, but also to start attacking chains. Despite being under immense pressure at different times, there were promising signs of what might come if the back group can spend more time together.

In Essendon’s victories against Melbourne, Sydney and Richmond, 19 of McKay and Reid’s 33 post-clearance contested possessions were intercept marks, well above their 2025 season averages of 2.5 for McKay and 2.1 for Reid. When the two control the air against their key forwards, there are so many flow-on effects possible.

When you take an intercept mark, it gives teammates time to get into position to help reset the field both defensively and offensively. Without that aerial support, the game stays in motion at ground level, leaving little time for teammates to assess what’s unfolding and relocate an opponent amid the chaos.

While McKay and Reid showed their potential as a pairing, having all three key posts available consistently will be crucial.

Over the last two seasons (46 games), Jordan Ridley has only played alongside both McKay and Reid in six full games, with two of the three featuring together a mere 21 times, a stark contrast to Adelaide, Geelong and Hawthorn’s intercepting defenders, who each played at least 16 of 23 home-and-away games together this year.

That level of stability allows a backline to gel across a season, building an understanding between teammates and improving their ability to work as a unit, a key example being recognising when to drop off an opponent to help cover in the air.

But what would help all defenders most is how the ball comes in from further up the ground.

Too easy in transition. After the previous two seasons, teams specifically targeted Essendon’s uncontested marks this year, and the challenge for 2026 is for the Bombers to return serve and improve on this clear weakness in their defensive game.

The issues were evident early, and when stronger teams exploit a vulnerability, the whole competition takes note, with opposition analysts marking it clearly as a priority.

Allowing 77 and 95 uncontested marks in the back two-thirds of the ground in their first two games at the MCG against Hawthorn and Adelaide, with roughly one in every three of those teams’ possession chains starting in their defensive 50 going unbroken up to the other end, was a major reason Essendon conceded over 100 points in both games. From that stage on, the question became whether the Bombers could correct this early-season vulnerability. Unfortunately, as we all lived through, they were unable to do so, particularly against the competition’s best sides.

In Part Four, Ball Movement, I detailed many of the issues that contributed to these problems. While some stem from player capabilities, coaching must also take responsibility for holding players accountable and designing a defensive setup that makes the team harder to play against.

The league’s better teams find easy outlets by working together to create space and reward those efforts to better control both tempo and pressure. Essendon’s tendency to allow those options means the ball continually shifts angles of attack, opening more space in the most critical part of the ground — the middle. This passive and reactive approach to defending has been one of the biggest obstacles holding the team back and requires urgent change. Coming up: Scoring How both Essendon and their opponents generated their score.

Comments